The History of How We Understand Depression

Depression, one of humanity’s oldest and most pervasive mental health conditions, has been interpreted through vastly different lenses across time — from supernatural punishment to chemical imbalance. Understanding how these views evolved reveals not only the progress of science but also the shifting ways societies have related to emotion, suffering, and the human mind. The history of depression is, in essence, a reflection of how civilization has struggled to comprehend sadness and despair — and how compassion, knowledge, and medicine have gradually replaced fear and stigma.

1. Ancient Civilizations: The Dawn of Melancholia

The earliest known descriptions of depression date back to Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt, where emotional disturbances were attributed to spiritual or demonic forces. Treatments involved rituals, prayers, and exorcisms rather than medicine or therapy. These early societies viewed mental distress as a sign of divine disfavor or spiritual imbalance.

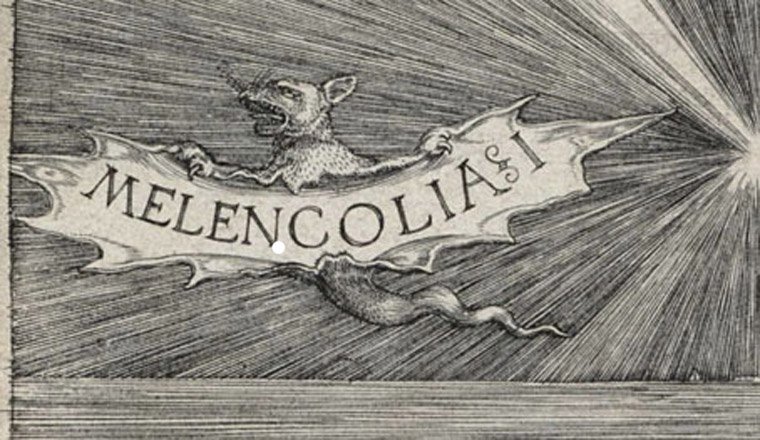

It was in ancient Greece that the concept of depression began to take on a medical dimension. Around 400 BCE, Hippocrates, the father of modern medicine, proposed the theory of the four humors — blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. According to this model, an excess of black bile caused “melancholia,” a condition marked by persistent sadness, fear, and insomnia. Though primitive by today’s standards, Hippocrates’ explanation was revolutionary because it located mental illness within the body, not the supernatural. His ideas introduced the notion that emotional suffering had natural causes, paving the way for medical inquiry.

Hippocrates’ successors, such as Galen, expanded on this humoral theory, prescribing lifestyle changes, diet, and rest as treatments. Although these methods were limited, they reflected an early understanding that mind and body were interconnected — an idea that still influences medicine today.

2. The Middle Ages: Sin, Faith, and Madness

After the fall of the Roman Empire, much of classical medical knowledge faded from Western Europe. The Middle Ages saw a resurgence of spiritual and moral explanations for mental illness. Depression, or “melancholy,” was often interpreted through the framework of Christian theology. Sorrow and despair could be seen as temptations from the devil or as punishments for sin.

One of the most influential ideas of this period was “acedia”, described by early Christian monks as a state of listlessness and spiritual apathy that hindered prayer and devotion. It was sometimes regarded as one of the seven deadly sins — sloth — though it likely described what we would now call depression or burnout. Treatments included confession, repentance, and isolation in monasteries.

Despite the dominance of religious thought, not all scholars abandoned rational inquiry. In the Islamic world, during the Golden Age (8th–13th centuries), physicians such as Avicenna (Ibn Sina) and Al-Razi preserved and expanded on Greek medical traditions. Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine described melancholia as a disorder of both the body and mind, emphasizing that emotions could influence physical health — an insight far ahead of its time. Hospitals in Baghdad and Damascus treated mental illness with music, baths, and compassion, centuries before such humane care appeared in Europe.

3. The Renaissance and Enlightenment: The Birth of the Mind

The Renaissance (14th–17th centuries) marked a rebirth of interest in human experience, art, and science. Thinkers began to question traditional religious interpretations of suffering. Writers like Robert Burton, in his monumental work The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621), described depression in rich detail, blending medical, philosophical, and literary perspectives. Burton proposed that lifestyle, diet, and emotional stress could all contribute to melancholy — showing an early recognition of what we now call psychosomatic interaction.

By the 18th century, during the Age of Enlightenment, a new rationalism encouraged physicians to study the brain and nerves. Depression began to be seen less as moral failure and more as a disorder of the nervous system. Terms like “nervous breakdown” and “hypochondria” emerged. Doctors such as George Cheyne and Thomas Willis suggested that lifestyle, stress, and emotional strain could weaken the nerves and cause melancholy — blending biology and psychology in new ways.

This period also saw the birth of psychiatry. The French physician Philippe Pinel (1745–1826) famously removed chains from patients at the Bicêtre Hospital in Paris, symbolizing a shift toward more humane treatment of the mentally ill. Pinel classified “melancholia” as a distinct mental disorder characterized by “prolonged fear and sadness,” introducing the idea that emotional disorders could be classified, studied, and treated scientifically.

4. The 19th Century: From Moral Weakness to Mental Disorder

The 19th century was pivotal in reshaping depression from a vague emotional state into a diagnosable medical condition. The rise of asylums across Europe and America provided spaces — albeit often harsh ones — for systematic observation of mental illness. Physicians began distinguishing between melancholia, mania, and psychosis, laying the groundwork for modern psychiatric diagnosis.

German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin (1856–1926) developed one of the first comprehensive systems for classifying mental disorders. He separated manic-depressive illness (now known as bipolar disorder) from schizophrenia, arguing that mood disorders followed predictable courses and had biological origins. His work laid the foundation for the diagnostic frameworks used today.

At the same time, social attitudes toward depression were conflicted. While doctors increasingly viewed it as an illness, society often regarded it as a sign of moral weakness, particularly in women. “Hysteria” became a common — and sexist — diagnosis for female emotional distress, while men suffering from depression were often told to work harder or show courage. Despite medical progress, stigma remained deeply rooted.

5. The Early 20th Century: Freud, Psychoanalysis, and the Unconscious

The 20th century ushered in profound changes in how we think about the mind. Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) proposed that depression, or “melancholia,” stemmed from unconscious conflicts — especially unresolved grief or guilt related to loss. In his essay Mourning and Melancholia (1917), Freud argued that while mourning was a natural response to loss, melancholia occurred when the mind turned anger inward, leading to self-reproach and despair.

Freud’s theories laid the groundwork for psychoanalysis, emphasizing talk therapy, introspection, and the exploration of childhood experiences. His ideas influenced generations of clinicians and introduced the concept that depression could be treated by addressing emotional and cognitive patterns, not just biology.

Other psychoanalysts, like Carl Jung and Melanie Klein, expanded these ideas, linking depression to broader themes of identity, attachment, and personal meaning. Although many of Freud’s concepts have since been revised or rejected, his emphasis on the psychological roots of depression permanently changed the landscape of mental health treatment.

6. The Mid-20th Century: The Biological Revolution

After World War II, psychiatry shifted toward biological explanations. Researchers discovered that certain drugs altered mood and behavior, leading to the development of antidepressants. In the 1950s, scientists studying tuberculosis patients noticed that a new drug, iproniazid, elevated mood. Soon, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and tricyclic antidepressants followed, supporting the idea that depression involved chemical imbalances in the brain.

This gave rise to the monoamine hypothesis, which suggested that low levels of neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine caused depression. Though later criticized as overly simplistic, it revolutionized psychiatry and provided the foundation for pharmacological treatments.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), first published in 1952, gradually refined the criteria for diagnosing depression. By the 1980s, major depressive disorder (MDD) became a distinct category, reflecting a shift toward evidence-based medicine and standardized care.

At the same time, social awareness grew. The post-war era saw a gradual move away from institutionalization toward community mental health, emphasizing rehabilitation and outpatient therapy. Depression began to be viewed as a common, treatable illness rather than a life sentence of confinement.

7. The Cognitive Revolution: Thoughts, Behavior, and Emotion

While biochemistry dominated psychiatry, psychologists in the 1960s and 70s began exploring how thoughts influence emotion. Aaron T. Beck, originally a psychoanalyst, noticed that his depressed patients held persistent negative beliefs about themselves, their world, and their future — what he called the “cognitive triad.” He developed Cognitive Therapy, later known as Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT), to help patients identify and challenge these distorted thoughts.

Around the same time, Albert Ellis introduced Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT), focusing on how irrational beliefs produce emotional distress. These approaches shifted the understanding of depression toward the interaction between mind and behavior, empowering patients to play an active role in their recovery.

The effectiveness of CBT was later confirmed through extensive clinical trials, and by the 1990s it became one of the most widely used psychotherapies for depression — often combined with medication for optimal results.

8. The Late 20th and Early 21st Century: The Biopsychosocial Model

By the late 20th century, scientists and clinicians began recognizing that no single theory could explain depression entirely. Instead, it emerged as a biopsychosocial condition — influenced by a complex interplay of genetics, brain chemistry, personality, trauma, and environment.

Research in genetics revealed that certain people are more vulnerable to depression due to inherited traits, but that life events such as loss, abuse, or chronic stress often act as triggers. Neuroimaging studies identified structural and functional changes in brain regions such as the amygdala and prefrontal cortex, while social scientists highlighted the role of isolation, inequality, and modern lifestyles in shaping mental health.

Public perception also began to change. In the late 20th century, celebrities and public figures started speaking openly about their experiences with depression, helping to reduce stigma and encourage treatment. Campaigns promoting mental health awareness reframed depression as a medical condition — common, treatable, and deserving of compassion.

Newer antidepressants like SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) became widely used, offering fewer side effects than earlier medications. However, debates arose about over-prescription, the placebo effect, and the need for holistic approaches beyond pharmaceuticals. The conversation expanded to include mindfulness, exercise, nutrition, and social connection as integral parts of recovery.

9. The Modern Era: Integrating Science, Technology, and Humanity

In the 21st century, the study of depression has entered a new frontier. Neuroscience, genetics, and digital technology are providing deeper insights than ever before. Researchers are exploring inflammation, gut microbiome, and hormonal factors as contributors to mood disorders. Treatments such as ketamine therapy, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), and psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy are showing promise for people who do not respond to conventional medications.

At the same time, mental health apps and online therapy platforms have made treatment more accessible. Artificial intelligence now helps detect early signs of depression through speech, writing patterns, and behavior — offering hope for early intervention.

Yet, even with all these advances, one lesson from history remains clear: depression is not just a medical condition but a deeply human experience. Understanding it fully requires empathy, community, and an appreciation of the individual story behind each struggle.

Conclusion

From the ancient belief in black bile to modern neuroscience, our understanding of depression has transformed from superstition to science, from judgment to compassion. Each era — whether guided by religion, reason, or research — has contributed a piece of the puzzle.

Today, we recognize depression as a multifaceted condition shaped by brain chemistry, thought patterns, and life circumstances. But perhaps the greatest progress lies not in the laboratory or the clinic, but in society’s growing willingness to listen, support, and understand those who suffer. The history of depression is still being written — and with each new discovery, we come closer to a world where no one faces their darkness alone.